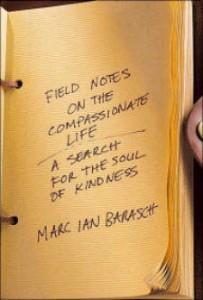

With extraordinary good timing, I arrived at the library shortly after someone placed Field Notes on the Compassionate Life: A Search for the Soul of Kindness on the New Books shelf. The jacket text boasted about “thrilling exploration” and “provocative questions” so I unhesitatingly tucked it under my arm and briskly walked the three steps to the checkout.

With extraordinary good timing, I arrived at the library shortly after someone placed Field Notes on the Compassionate Life: A Search for the Soul of Kindness on the New Books shelf. The jacket text boasted about “thrilling exploration” and “provocative questions” so I unhesitatingly tucked it under my arm and briskly walked the three steps to the checkout.

The book lived up to its promises. In the days that followed, Marc Ian Barasch’s writing grabbed me like a bear hug as I slowly became convinced this book is indispensable to the Shambhala Warrior library—or anyone’s library, for that matter.

Written in an engaging, compelling style (similar to Derrick Jensen’s, yet with hope instead of anger), with a perfect balance of anecdote and reflection, this book offers multiple and diverse windows through which to view the heat of compassion. It also offers a generous dose of cooler insight, as Barasch provides analysis, unpacks and scrutinizes his assumptions, and asks strategic questions.

A couple of predominant ideas weave their way through these chapters. One is based on seeking ways to foster a shift in perception, along with finding and interviewing people who have, in some way, achieved such a shift in their lives. This shift is defined as an ability to see, and feel, “you-in-me” and “me-in-you” – essential to compassion.

Another key theme is the notion that perhaps humans are evolving toward increased compassion, which is certainly a refreshing idea to spend time with, as we live in our war-weary world, immersed in our Super-Bowl, super-size culture.

“A society based on universal compassion is not just our only hope; it is an evolutionary imperative,” Barasch writes. Does his statement resonate with you, as it does with me?

An early chapter is devoted to our close cousins, as Barasch visits the Yerkes National Primate Research Center and the Language Research Center, well known enclaves of chimps and bonobos who are nearly human in their development and socialization. He is searching for “clues to the interplay between selfishness and kindliness that keeps our own species scratching its head.” He finds such clues, and describes the process with warmth and humor.

Not surprisingly, Barasch brings Charles Darwin into the discussion of evolutionary trends. We are informed of a little-known fact, that in Darwin’s Descent of Man there are ninety-five mentions of “love” but only two of “survival of the fittest.” According to Barasch, Darwin’s writings “are filled with admiring accounts of animal reciprocity, cooperation, and even love.” Gee, why didn’t I learn about this in school?

Other points worth pondering are raised by Barasch as he reflects on time spent with unusual people – children who have Williams’ syndrome (an affliction that is accompanied an extraordinary sense of empathy), adults with Asperger’s syndrome (a form of autism characterized by a lack of empathic ability), and altruistic kidney donors who are motivated to sacrifice an organ from their own body to relieve the suffering of an anonymous person.

Perhaps the most dramatic story he uncovers is that of a father whose beloved daughter was brutally killed but who, instead of demanding revenge, went on to forgive and then befriend the murderer. (I read this account with tears streaming.)

Another chapter finds Barasch living voluntarily as a homeless bum in Denver for a week, on a “street retreat” organized by the Zen Peacemaker Order. These men choose to learn humility in a whole new way, as they bear witness to the many haunted souls struggling to survive.

There is much overlap between Barasch’s investigation of heart-opening and the teachings of The Work that Reconnects. He refers to Earth-dwellers “living through a Great Transition.” This makes me want to telephone him to say, “it’s often called the Great Turning; check out Joanna Macy’s work.” (And I’ve also just learned of David Korten’s book, due to be published in May 2006, called The Great Turning: from Empire to Earth Community – surely the concept is on the verge of becoming more widely known).

I also have a gripe. Although furnished with end notes, a bibliography, and an index, the 356 pages seem incomplete to me because of notable omissions. I’d like to suggest that if this book has a flaw, it is the lack of ink given to women’s achievements. It is almost as though Barasch is working from an unstated assumption: Everyone knows women are compassionate anyway, so let’s focus on some extraordinary men because it will have more impact. Just a small handful of women authors and researchers appear here among myriad male experts and sages.

Despite the “male-expert factor,” I purchased a hard copy to re-read, mark up and share, and I plan to keep an eye out for other works by Barasch. He’s definitely worth the investment.